Only very little is known about Jewish families settling in the Solingen area before the 18th century. The necessary number of ten religiously mature Jews to be able to conduct a complete religious service was most probable not reached before the second half of the 18th century. In the year of 1787, Michel David and Coppel Samuel bought a house in Südwall (Street), which was used as a synagogue until 1872. However, a first Jewish burial space existed already in 1718.

The Jews living in Solingen predominantly worked as butchers or merchants. Only caused by the Napoleonian Supremacy (1806 – 1813) they did not just gain political equality, but at the same time the privileges concerning craftsmanship were cut back, so that they were allowed to become an active part in the production of Solingen steel goods and in the export trade of weapons.

In 1854 the Solingen Jewish community was formed to be a public body. In 1857 the community of Opladen was associated, but stayed mainly independent. The chairman of the representatives became Gustav Coppel from Solingen, and his brother Arnold Coppel became the chairman of the board.

For a long time one of the community’s permanent problems concerned the appointment of a teacher and cantor. A rabbi did not exist in Solingen, so that this litanist was forced to take over manifold tasks. Unfortunately his payment was extremely low so that the money for the job was hardly enough to live on. Accordingly only a few candidates stayed for longer than just a few months. Only when the community council gave up the celibacy as compulsory in 1884, Max Joseph was found as a teacher, who stayed in office for several decades.

In 1861 the community bought a house in Malteser Street, because the building in Südwall had become much too small as a synagogue for the growing number of inhabitants. However, the financing of the new building dragged on over several years, so that the neoromanic domed building providing 150 seats for men and 80 seats for women, a classroom and a flat for the teacher could only be inaugurated on March 8th in 1872. It was a solemn ceremony culminating in a festival procession joined by the town’s notables as well as Solingen’s population.

The social emancipation of Solingen’s Jews was well advanced. It was especially Gustav Coppel (1830 – 1914), who held a position of high social acceptance in the town’s life. The producer of steel goods was, among others, politically active as town councilor, district chairman of the National-Liberal Party, and president of the local chamber of commerce. Apart from this he supported those people, who were unable to profit from the economic upswing with his charitable generosity. Together with his brother Arnold he founded the ‘Coppelstift’ in 1906, which took up its work in the field of family welfare in 1912, and today known to be the earliest child guidance office in Germany.

Towards the end of the 19th century the Solingen Jews’ main line of business shifted to the sector of textile trade. More and more clothing stores were located in Kaiser Street (today: High Street). The same happened in Ohligs in Düsseldorf Street after the turn of the century.

During the First World War Jewish volunteers fought alongside with Christian soldiers for their home country, and after the defeat in 1918 they also had to suffer from the immense economic burden caused by the war debts. This was the reason why the synagogue parish could not afford pensioning off their teacher Max Joseph.

The population census of 1932 showed the number of 265 Jewish inhabitants, which meant to be an 0.2% share of the population. By June 1933 this share had already diminished to 0.14%. Many Solingen Jews leapfrogged the fatal persecution by Nationalsocialism by emigration. Nevertheless, the membership list of October 1938 still consisted of 89 names.

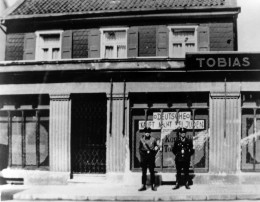

During the pogrom night between the 9th and the 10th of November the synagogue and the cemetery chapel as well as the numerous Jewish shops and private residences were looted and destroyed. The editor Max Leven was murdered, 32 Jewish men were arrested and most of them taken to the Dachau concentration camp followed by the imposed Aryanisation of all Jewish businesses and the extensive deprivation of any economic basis of existence whatsoever aiming at forcing the Jewish population into emigration.

The town of Solingen ‘bought’ the ruins of the synagogue at the costs of its demolition from the community, which just existed as a registered society. Until the ban of emigration in October 1941 a small number of Jews succeeded in fleeing abroad. After that the deportations to the east began. In July 1942 the remaining board members were deported to Theresienstadt, among those were the chairman Dr. Alexander Coppel and the former treasurer Georg Giesenow. Together with six other Jews, until then protected because of their interreligious marriages, the physician Dr. Emil Kronenberg was also deported to Theresienstadt.

The 80-year-old Kronenberg lived to see the liberation of the concentration camp in May 1945 and returned to Solingen, like also the children’s doctor Dr. Erna Rüppel, who, after having been divorced from her Christian husband, had gone underground.

The by far largest group of Solingen’s Jewish population, however, had been expelled or murdered, and the originally prospering and blooming community life had been extinguished.

Today the Jewish Religious Community of Wuppertal, which Solingen is part of, consists of more than 2.000 Members, the most of which stem from the former Soviet Union.

After Wilhelm Bramann’s “Jewish History of Solingen” in Michael Brocke’s “The Jewish Cemetery at Solingen”, Solingen, 1996.